In this article

With reward-based training and positive reinforcement being the focal approach for modern dog trainers, being clear on what “reward” and “reinforcement” mean is crucial if you hope to train a dog successfully and efficiently with purely non-aversive methods.

Although many use these terms interchangeably, they aren’t as mutually inclusive as you might think. Keep your teaching sessions and diction on point by learning the essential differences between reward and reinforcement in dog training.

Visual Differences

At a Glance

- A beneficial reinforcer that pleases your dog

- Can be a treat, toy, play, or praise

- Allows dogs to make decisions

- A response that supports a particular action

- Increases the likelihood of a behavior happening in the future

- Repetition builds reliable behavior

Overview of Reward Training

Rewards are positive outcomes that dogs receive for a desired behavior. In traditional training sessions, the most common reward is a tasty treat. We use reward as a form of positive reinforcement, giving prizes for good behavior so our dogs will associate it with enjoyable results and make that behavior more probable.

Although we often think of rewards as the special treats provided when our dogs obey us, we must remember that there are other forms of rewards.

Different Types of Rewards

Rewards are anything your dog enjoys, typically defined as objects or events that elicit an approach rather than a withdrawal response. They can be food treats, toys and play, or simple affection offered when our dogs follow a command or show proper manners.

All dogs differ in their motivations, and it’s up to the owner to find what their dog wants more than anything, whether it’s a few pieces of dehydrated chicken or a vigorous game of tug-of-war. Other rewards can be within the environment. We can reward a particular behavior by letting our dog sniff around an area of the park, run outside to play, or meet a new visitor.

Rewards are not always in our control. Interaction with a nearby dog or chasing a squirrel can be gratifying, even more so than the treats we have on hand. Keeping the rewards you control more appealing than anything else in the environment is essential for successful training.

How Rewards Work

Our dogs choose rewards. Although we may think that actions like pats on the head or cooing praise are meaningful to a dog, they may not find any value in them. If the dog has anxiety and doesn’t know you, they could even find these “rewards” to be scary and stressful.

A reward may also gain or lose value depending on environmental factors, time of day, or your dog’s mood. For example, the prospect of food may be more valuable for a hungry dog than for one that just ate. Using the most desirable rewards for your dog will help maintain their attention and facilitate faster learning.

- Provide influence over a dog’s actions

- Enhance dog-owner bonds

- Encourage better decision-making

- Don’t use coercion to force action

- Can be difficult to identify

- May reinforce unwanted behaviors

Overview of Reinforcement Training

While rewards follow a desired behavior, reinforcement refers to the connection between rewards and behaviors. Reinforcement incorporates stimulus-response memory and conditioned responses. Dogs don’t need to learn what’s rewarding.

You don’t need to tell your dog that a piece of cheese is desirable or that they’d enjoy a game of fetch. However, with reinforcement, they can learn that particular actions will result in a reward, strengthening the perceived benefit of that action.

Different Types of Reinforcement

A primary reinforcer is what we commonly consider a reward. For example, your dog sits when you say “sit,” and you use a clicker to let them know that it’s a job well done. With repetition, this reinforcement teaches that good things happen when they perform a particular behavior.

Timing is critical to correctly applying reinforcement, and one of the primary reasons is that it’s easy to reinforce the wrong behaviors. Our reinforcement must come when the behavior occurs or at least within a few seconds. Otherwise, the dog may connect the reward with the incorrect behavior or become confused about what you’re rewarding.

Secondary Reinforcers

You can add secondary reinforcers to properly time the reinforcements and help your dog build the stimulus-response association. Unlike primary reinforcers like food or toys, which already have value for reinforcing a behavior, a secondary reinforcer needs a history of positive association with a primary reinforcer to make it rewarding by itself.

An example of a secondary reinforcer could be a marker, such as the click of a clicker or a verbal “yes.” We can’t always retrieve and give a treat to our dogs exactly when they do something desirable, but it’s easy enough to say a word or click a clicker to mark a moment precisely. You can then give a reward to encourage your dog to repeat that behavior.

While dogs see no inherent benefit of a random word or the sound of a clicker, charging the reinforcer gives it an independent value. We say the marker word and immediately offer the reward. Repeat this enough times, and your dog will eventually understand the marker-reward connection. In the training context, its proper timing tells the dog, “Good job! That is the exact behavior that results in rewards.”

Importantly, primary reinforcers must follow secondary reinforcers as often as possible. Without the real reward supporting the arbitrary marker, our click or marker word can lose value and no longer reinforce actions.

Understanding Reinforcement

Whether we realize it or not, dogs never stop learning and adapting to ensure survival and put them in the most beneficial position possible. They constantly create associations, using reinforcement and punishment in stimulus-response chains to guide their behaviors. As owners, we must understand what motivates our dogs and how we reinforce their desirable and undesirable actions.

For example, if your dog starts lunging on the leash and barking when they see another dog while on a walk, it could be due to a desire to greet the other dog or get away from them. Turning and taking your dog out of the situation can subsequently reinforce if your dog is scared of the other dog or punish if they want to play. One promotes barking and lunging, while the other discourages it.

When you know which action is rewarding, you can use it to consistently and constructively reinforce or punish behaviors, which can easily turn into habits. If you don’t know what your dog wants, you may support the idea that lunging, barking, and being aggressive is how they should act to get what they want.

- Invokes memory and inspires learning

- Increases the likelihood of a behavior being repeated in the future

- Often occurs without the handler’s awareness

- Could also increase unwanted behavior

- Can include aversive use

How Rewards Relate to Reinforcement

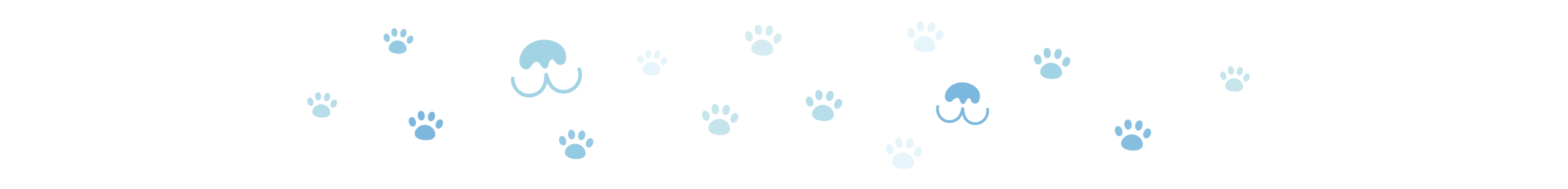

In dog training, we have four methods of operant conditioning to teach behaviors:

- Positive reinforcement

- Negative reinforcement

- Positive punishment

- Negative punishment

The term “reinforcement” refers to how we promote a given behavior and make it more likely to occur in the future. Punishment is when we teach that a particular behavior is undesirable and not one to repeat. Negative means we remove something, while positive means we supply something.

Among these, punishment requires some clarification. Punishment should never involve withholding food and water, physically striking your dog, terrifying them, or screaming at them. Instead, it should be used carefully and productively. For example, it can be a simple time-out in a safe crate. It can also be in the form of ignoring your dog when they’re doing something undesirable.

Within these training techniques, both aversives and rewards are commonly included. Rewards apply to certain types of reinforcement and punishment, as do aversives that inflict unpleasant consequences, such as e-collars or prong collars.

Rewards are the basis of positive reinforcement, as when we give our dogs a treat to reinforce them obeying a command. We can also use rewards with negative punishment, discouraging unwanted behaviors by removing something they want.

An example of this might occur when you want your dog to wait in a sitting position before leaving the house for a walk. If they jump up and move to the door before you release them, you can close the door, removing access to the outdoors where they want to go.

Maybe your dog pulls on the leash to get to something they want to sniff. You stop walking when they pull and only move forward when they relax. We remove something desirable to punish the behavior, showing the dog the negative consequences so they don’t do it again.

Reward vs. Negative Reinforcement

Reinforcement doesn’t always involve rewards; it only means you try to promote a particular behavior. With negative reinforcement, you teach the proper behavior by applying an aversive sensation and taking it away when your dog does something desirable.

A frequent application for this technique is the force fetch hunters use to train their dogs to get them to retrieve. They apply pressure with an uncomfortable action, like an ear or toe pinch. When the dog takes the desired object in their mouth, the handler removes the pressure and discomfort. The dog learns that taking the object leads to relief, making them more likely to do the action in the future.

Using Reward vs. Reinforcement

While reward-based training only uses objects or activities your dog likes, either by offering or withholding them, reinforcement can use rewards or aversives, the latter being more challenging for dog owners to use at home.

Aversives in positive punishment and negative reinforcement can be effective but also dangerous. When used incorrectly, they can damage the dog-owner bond and increase the dog’s aggression and aloofness. Fallout happens when dogs engage in escape or avoidance behaviors to evade unpleasant experiences.

Dogs can develop unwanted habits, become less motivated and trusting, and lose confidence, making training much more difficult. While dogs may accept failure and eagerly continue working when you only offer rewards, aversives often shut them down and make them afraid to try new things.

If you are concerned about your dogs behavior, we suggest you speak with a vet

If you need to speak with a vet but can't get to one, head over to PangoVet. It's our online service where you can talk to a vet online and get the advice you need for your pet — all at an affordable price!

Conclusion

Rewards can appear as part of punishment, and aversives can act as reinforcement. Although we tend to mix rewards and reinforcements without much consequence, understanding the difference has crucial implications during training and when we discuss our efforts with others.

While rewards are more straightforward and safer for novice trainers, using reinforcement requires appropriate timing, appreciation for nuance, and consistency to build the proper behaviors without harming your dog’s trust and respect for you.

Featured Image Credit: (L) miroha141, Shutterstock | (R) otsphoto, Shutterstock