In this article

While we may not recognize it at every moment of the day, our dogs never stop learning. They’re ceaselessly creating new associations, learning which behaviors cause which responses to understand the best, most efficient ways to get what they want or need.

The constant connection-building can make everyday training seem more complicated than many owners may have initially thought. Every movement and interaction can be meaningful, making it crucial to appreciate how much we reward and punish our dogs at every turn to shape their behavior. On the other hand, it also opens up previously unseen opportunities.

Such is the premise of the Premack Principle. In the 1950s, psychologist David Premack presented his theory that high-probability behaviors reinforce low-probability behaviors. Through various experiments, he revealed that desirable outcomes can help us train desired habits, a concept canine experts continue to apply today.

How Does It Work?

Premack defined the Premack Principle (or the differential probability hypothesis) as follows: “Any response A will reinforce any other response B, if and only if the independent rate of A is greater than that of B.”1 More probable behaviors (i.e., things the dog wants to do) can reinforce less probable behaviors (things you want your dog to do).

The idea is that behaviors can promote other behaviors. Depending on the circumstances, some behaviors will be more desirable than others. You can discern this by finding those activities that dogs enjoy the most. In essence, they are typically behaviors they’ll do more often, or more willingly than others.

Dogs have a hierarchy of behaviors that can strengthen or weaken other responses depending on where they fall in this low-probability/high-probability spectrum. If a dog performs one behavior at a higher rate than another, it can be a reinforcer for that other behavior. It can also work the other way. A lower probability behavior can punish an immediately preceding higher probability behavior to make it less likely.

Response Deprivation

The order of high and low probability behaviors can change if dogs feel satisfied or unsatisfied. A concept related to the Premack Principle called the response deprivation theory suggests behavior A can reinforce behavior B if the dog has restricted access to behavior A. The desired behavior is contingent on the less desired behavior. For example, if a dog is deprived of food, (something that should never happen by the way) they’ll be more likely to do something if it means they get to eat.

With any behavior, dogs have a baseline level of performance they’ll display when they have open access to the behavior. For instance, a dog may sniff the ground for 10 minutes if they have unrestricted access to it. Response deprivation indicates that keeping them from sniffing can maintain their desire for it (since they aren’t meeting their baseline, or “bliss point,” for sniffing). Sniffing can then reinforce a less desirable behavior by being a contingency.

Response suppression and deprivation are vital in maintaining a dog’s motivation for one behavior over another. If a dog does one thing more than another with free access to both, excessive access to the more preferable behavior can make it less reinforcing to the dog.

Dogs love treats, but they’ll get tired of them eventually if you give them too many. Eating them can then become a lower probability behavior, making it less motivating when executing commands and other desired actions. When using the Premack Principle, maintaining high-probability behaviors means restricting them so your dog wants them more.

Contingency and Changes in Behavior Preference

The hierarchy of behavior probability can shift from one minute, hour, or day to the next. It depends on which behaviors your dog can satisfy and which behaviors you suppress. A dog with a full belly will be less motivated to eat food than a hungry dog, and a dog that has sniffed around for an hour will be less motivated to keep doing it than a dog that hasn’t gone outside at all.

Satisfying or depriving a behavior subsequently affects the work a dog will be willing to engage in. Each behavior has a “bliss point”, an amount of time the dog will spend doing it if they have free access. For example, a dog may be satisfied with an hour chasing squirrels but only 15 minutes playing tug of war.

You can see how behaviors can change in probability by being aware of these bliss points and how much your dog has been satisfied.

Where Is the Premack Principle Used?

The Premack Principle is applicable in numerous working and companion behaviors. It can motivate dogs in scent detection, search-and-rescue, and other crucial professional capacities or during sports, such as Schutzhund or agility.

When owners adopt the Premack Principle, dog training opportunities appear frequently during the day. Impulse training incorporates it. “Learn to earn” centers on it. If you’re training a challenging working breed, like a Siberian Husky, it is an excellent way to establish your leadership and make focus a core habit. When you understand your dog’s favorite activities, the Premack Principle can make them fun and productive.

An example of the Premack Principle at work may be how you train recall and use it at the dog park. Your dog wants to play with other dogs. If you perform a recall and put them in the car, you would be punishing the desired behavior with a low probability behavior. By contrast, if you perform a recall and give your dog a treat and release them for more play, you’ll reinforce the recall and make your dog more likely to do it later.

How Can You Use the Premack Principle

The Premack Principle works with a dog’s natural drives, encouraging numerous opportunities for rewarding good behavior. Watch your dog, and record the activities they enjoy the most. Some of the top activities for many dogs include:

- Sniffing while out on a walk

- Chasing toys

- Playing tug of war

- Swimming

- Playing with other dogs or children

- Going for walks, jogs, or hikes

- Digging holes

- Herding

- Snuggling or receiving pets

- Getting belly rubs or massages

- Receiving praise

- Eating tasty treats

Don’t focus on behaviors you wouldn’t want your dog to perform. Calming down or performing a sit shouldn’t open the chance for them to dig through trash or rip into a couch cushion. Use only positive enrichment behaviors to encourage proper behaviors, whether sitting politely while waiting for their food, loose-leash walking, or staying calm when a stranger knocks on the door.

Stay consistent with how you offer high-probability behaviors as rewards. Restricted access makes them more desirable for your dog, so ensure you use enjoyable activities as training rewards each time. Don’t offer them if your dog doesn’t fulfill your requirements. By making them contingent on lower probability behaviors, like giving you attention, staying calm, or performing a command, you’ll make those more desirable actions automatic, increasing their value as a reinforcer to less fun or desirable behaviors.

Conclusion

The Premack Principle gives us a broader perspective on training, revealing how frequently opportunities for positive reinforcement appear. It highlights the win-win aspect of practical training. When our dogs do what we ask, they get what they want, and everyone benefits from happier relationships and a more fulfilling routine.

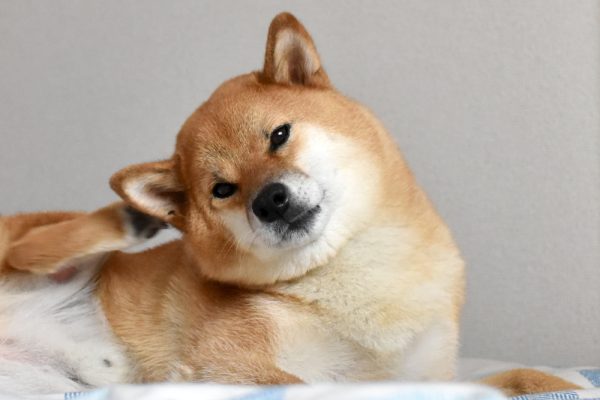

Featured Image Credit: kathrineva20, Shutterstock