Have you heard of the Kingdom of Bhutan? This small country is nestled in the Himalayas between Tibet and India and is well-known for how it managed to keep its stray dog population under control. Like much of Asia, which has roughly 300 million stray dogs, dogs living in the street were abundant in Bhutan. And like most other countries with sizable stray canine populations, Bhutan was at a loss about what to do about the problem.

So, what solution did Bhutan land on for keeping its stray dog population under control? Unlike America, where most stray dogs are caught and taken to shelters where they are either adopted or eventually euthanized, Bhutan wanted to find a way to control the dog population that fell in line with Buddhist teachings (as Buddhism is the religion of Bhutan).

Thus, in 2009, they began a country-wide catch-neuter-vaccinate-release (CNVR) program.1

The Problem

The stray dog community in Bhutan is large, and although for the most part, these canines live in harmony with their human counterparts, there is the risk of dog bites and the spread of rabies (as the dogs had never been vaccinated). The World Health organization estimates that globally around approximately 59,000 people a year die due to rabies, and most cases of rabies in humans are due to a dog bite.

The problem was not only that, though, but also the state of tourism in Bhutan in 2009. Not long before 2009, much political reform and modernization occurred in Bhutan. Included in this was the introduction of television and the internet in 1999, as well as a switch from a monarchy to a constitutional monarchy. And though tourism in Bhutan has been around since 1974, the number of tourists started rising in the late 1990s. However, some tourists began complaining about all the stray dogs that were around, commenting that they were incredibly noisy. Tourists were also afraid to walk around at times due to all the canines.

So, there was more than one societal and animal welfare issue at play in the decision to control the dog population.2

The Solution

Bhutan was eager to find a humane solution to the stray dog problem that aligned with the country’s Buddhist values. So, in 2009, the country reached out to Humane Society International (HSI) to help implement a solution. HSI facilitated the CNVR program with the goal of sterilizing all stray dogs in the country. It was launched in February 2009, and in a matter of months, 2,800 dogs were sterilized.

However, there was a shortage of vets who could perform sterilization procedures when the program began. HSI offered some veterinary help, and the government encouraged people to take up veterinary studies

There were also dog catchers, vet assistants, and volunteers who helped by aiding veterinarians in their jobs or by capturing dogs and bringing them in to be sterilized and vaccinated.

The Outcome

Clearly, Bhutan was having success in getting plenty of stray dogs sterilized even in the early days of the program, but what was the final outcome?

In 2023, it was reported that Bhutan had achieved its goals and sterilized and vaccinated every stray dog in the country! It may have taken 14 years, but the country ended up sterilizing and vaccinating around 150,000 dogs; they also microchipped 32,000 pet dogs while they were at it. This means the stray dog population is currently under control, and the risk of rabies has diminished.

We guess you could call that a major success!

Conclusion

Bhutan is a country in the Himalayas that wanted to control its stray dog population humanely. So, working with HSI, they began a CNVR program that ran for 14 years. As a result, they ended up sterilizing and vaccinating every stray dog in the country! The program was carefully planned in phases and was a clear success, and other countries struggling with stray dog populations might want to take note.

See also:

- Can a Food That Sterilizes Dogs Solve the World’s Stray Problem?

- Is It Okay to Feed Stray Dogs? Vet-Approved Reasons & Advice

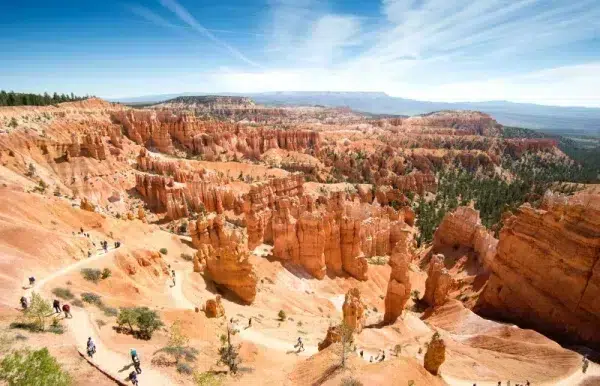

Featured Image Credit: Anton Gvozdikov, Shutterstock