Lassie, Rin Tin Tin, Old Yeller, Benji — when one thinks of famous dogs, these names immediately spring to mind. But among San Franciscans, Bummer and Lazarus are still honored 150 years after they roamed the streets of the city. Who were they? Bummer and Lazarus were stray mongrels in a city overrun by wild dogs. Yet their friendship, courage, cunning, and talent have allowed their fame endure.

Bummer was the first to appear. A stocky black-and-white Newfoundland mix, he was originally brought to San Francisco from Petaluma by a reporter for the Alta California, according to historian Malcolm E. Barker in his definitive book Bummer and Lazarus: San Francisco’s Legendary Dogs. By all accounts, a loner with a lumbering gait and protruding teeth, he would witness a dog fight in January 1861 that would change his life. A yellowish-black dog was engaged in combat with a much larger dog, the smaller dog enduring an injury to his leg. Hearing the battle, Bummer rushed in and chased the attacker off, escorting the smaller dog to a doorway. Bummer would care for his newfound friend, soon to be known as Lazarus, bringing him food he begged for from the saloons on Montgomery Street until his health improved. From that day forward, Bummer and Lazarus became inseparable friends.

They soon endeared themselves to the local merchants because of their talent for catching rats in a city teaming with the rodents. By one account, the dogs killed over 400 rats in one session when a downtown fruit stand was cleared in January 1863. Merchants recognized the dogs’ skill and would reward them with food to keep their establishments vermin-free. Local reporters, always on the lookout for a sensational story, began reporting on Bummer and Lazarus. Newspaper reports even exist of the dogs stopping a runaway horse and wagon.

Their fame grew due to the work of lithographer Edward Jump, whose satirical work was featured in local newspapers and store windows. It was from his lithograph The Three Bummers that the most enduring story about the dogs took hold. In 1859, a prominent San Francisco merchant named Joshua Norton, who had lost his fortune in a bad investment, declared himself Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico. Everyone in San Francisco went along with the idea and indulged him for the next 21 years.

Emperor Norton, as he became known, could be seen walking the streets in a lavish uniform, sporting a top hat decorated with feathers. He ate in restaurants for free and even printed his own money. Jump’s lithograph depicts Emperor Norton enjoying a sumptuous buffet in a saloon while Bummer and Lazarus look up at him, awaiting their share. There are also enduring reports that the dogs followed the Emperor everywhere and had seats in the theater reserved next to his. Other reports say that when Emperor Norton saw The Three Bummers, he tried to smash the window where it was displayed.

Stray dogs were everywhere in 1860s San Francisco, and in April 1862, the Board of Supervisors passed a law requiring the dogcatcher to round up any un-muzzled dogs, and if they went unclaimed, they would be destroyed. The merchants, who came to rely on the dogs, were concerned. Lazarus was caught by the dogcatcher and redeemed by a merchant. An effort was launched to spare Bummer and Lazarus from any further jeopardy. After considerable lobbying, the Board of Supervisors passed a special law on June 17, 1862, giving the dogs free reign to roam where they pleased. Reportedly, Bummer and Lazarus were sitting outside of the meeting chamber when the law was being considered, although no one knows how they got there.

Bummer and Lazarus’ freedom was to be short-lived. In October 1863, Lazarus died after eating food laced with poison. His death made headlines, and his body was sent to a taxidermist. His obituary in the Bulletin newspaper read: “Bright dogs never die! Lazarus sits in state, looking more natural than he did in life.” An Edward Jump lithograph depicts an elaborate funeral, with Emperor Norton, dressed as the Pope, presiding, swinging a dead rat over the dog’s carcass.

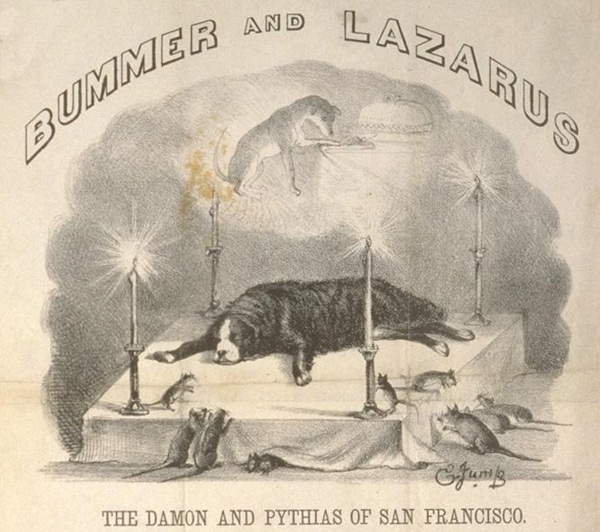

Bummer would live for another two years, eventually succumbing to injuries from a vicious attack by a drunk. His passing would go no less unnoticed by the press, and included an Edward Jump lithograph of Bummer lying atop a bier, surrounded by rats as Lazarus looks down upon him from heaven. Mark Twain would write of Bummer’s death, stating that the dog had died “full of years, and honor, and disease, and fleas.” Bummer’s carcass was also stuffed and he and Lazarus would be displayed in saloons for years, but the whereabouts of their pelts are unknown and were probably destroyed in the earthquake and fire of 1906.

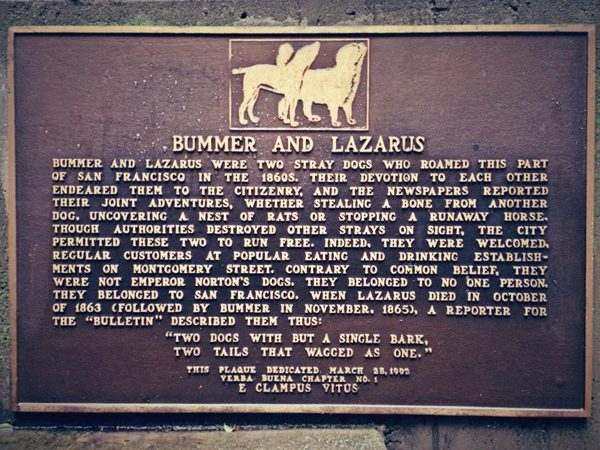

In 1992, the lives of the dogs would be forever immortalized by the placement of a plaque by the ancient and honorable order of E Clampus Vitus, a fraternal organization dedicated to preserving history, in San Francisco’s Transamerica Redwood Park. It reads: “Their devotion to each other endeared them to the citizenry. They belonged to no one person; they belonged to San Francisco. Two dogs, but with a single bark, two tails that wagged as one.”

About the author: Joseph Amster is an author, historian, and tour guide based in San Francisco. He is often seen walking around the city reenacting the legendary Emperor Norton for his Emperor Norton’s Fantastic San Francisco Time Machine tour, which takes visitors on a journey through San Francisco history as seen through the eyes of Norton I, Emperor of the United States and Protector of Mexico. He also offers San Francisco Food Safari, a culinary shopping tour of the Mission and North Beach neighborhoods.

Read more stories about famous dogs in history:

- The Most Loyal Dogs in History

- We Remember Guinefort, the Greyhound Who Was a Saint

- Dogster Hall of Fame: Druzhok, Pavlov’s Best-Loved Dog

- Meet St. James the Greater, the Patron Saint of Vets

- Rin Tin Tin: The Dog, the Legend

- Remembering Robot, the Dog Who Discovered a Trove of Prehistoric Art

- Remembering Laika, the First Dog in Space

- A Pet Columbarium Is Planned for a Church Named After St. Francis