In this article

View 3 More +It’s amazing how far we have come with space exploration since the whole thing first began. Did you know that animals have helped us explore space along the way?

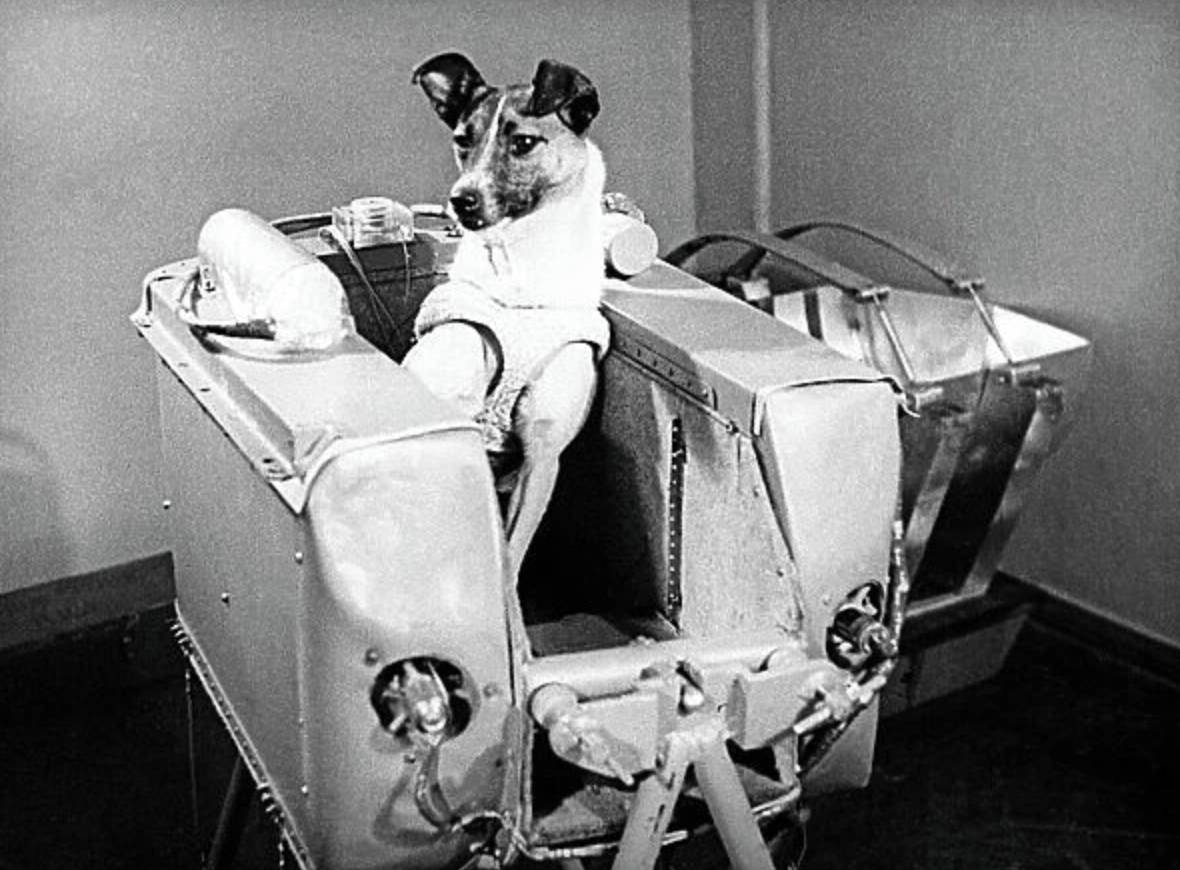

If you’ve recently heard about Laika, the space dog, you might want to know more about her, her breed, and the entire back story. You’re in luck. We’re here to discuss the different aspects of a smart little furry girl named Laika. Laika was a medium sized, mixed breed dog that likely contained genetic traits of Samoyed, Terrier, Husky, and Nordic breeds.

Laika: The Story Told Too Infrequently

We celebrate many milestones with space exploration history. However, many of you might not have ever known that the very first creature to ever orbit the earth was a furry four-legged friend named Laike, the first dog to go to space.

On November 3rd, 1957, the Sputnik 2 was launched. Inside, a brave little pooch set off with it. She was located on the streets of Moscow, cold, hungry, and homeless.

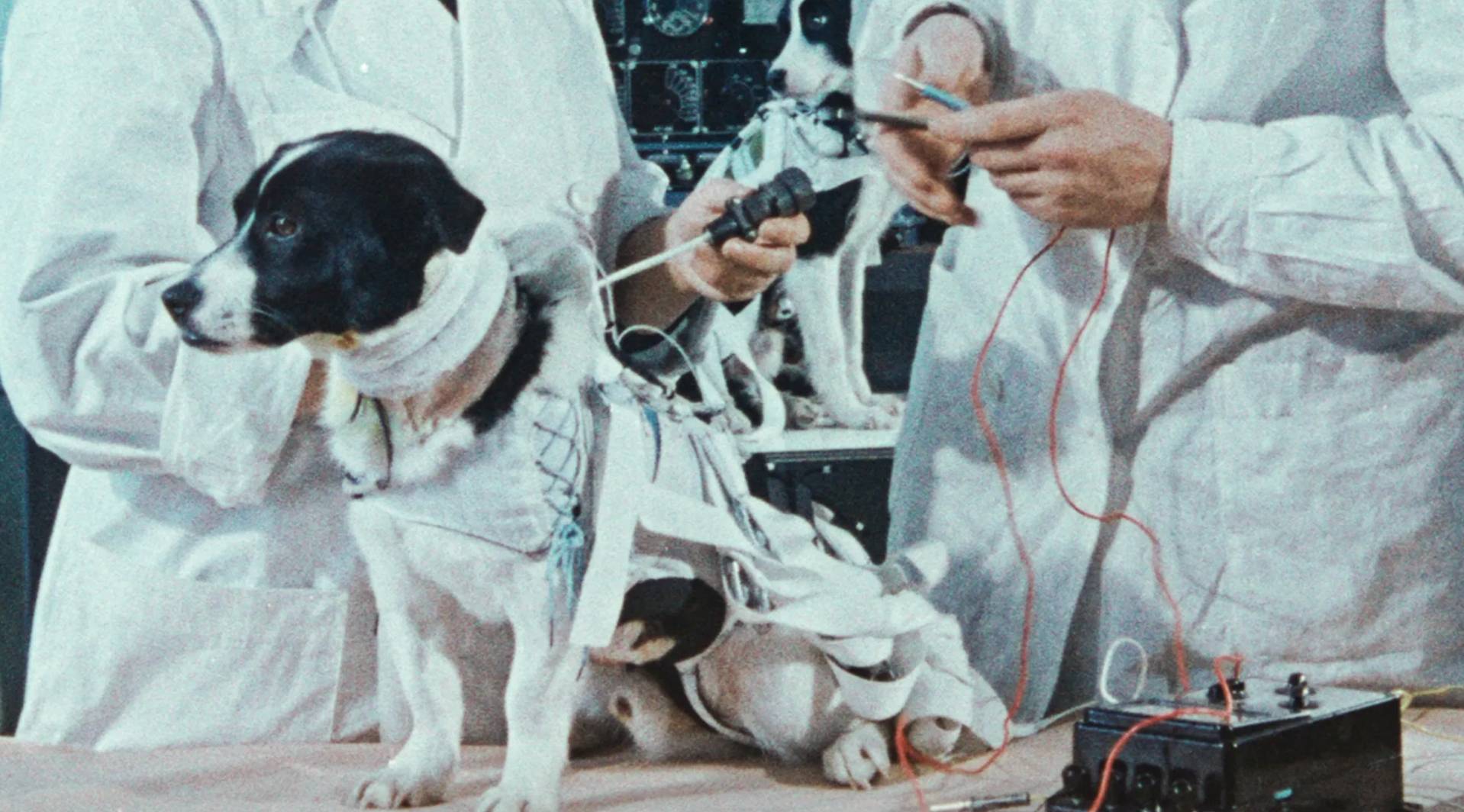

Despite her checkered past, it is said that Laika was a very even-tempered, mannerly little girl with a wonderful temperament. Was Laika an extensively trained, incredibly intelligent dog with years of experience prior to takeoff? Would she be well missed by all those she left behind her on earth?

The answer to this is a terrible and resounding no. Laika was merely a street dog found on the streets of Moscow. The folks that launched her up into space knew that she likely wouldn’t return to Earth. They were sending her out to space, placing her into orbit where she only lived a few hours.

How Did Laika Die?

There are various reports of how Laika died. Some reports from around the time of the incident state that she died due to oxygen starvation after being launched into space. But more recent reports say that she more likely died from overheating due to Sputnik 2’s cooling system failing. How old was Laika when she died? It is estimated that she was around 3 years old.

Is the Story of Laika Animal Cruelty?

There are many stories like Laika’s out there. Animals are used for testing in various ways by human beings all the time. This raises the question of whether sending a dog into space knowing it faces certain death is animal cruelty?

Any animal lover would not hesitate to say yes. Unfortunately, we try to learn new things about the world around us by using animals instead of humans to preserve our own humanity. However, in doing so, we tend to exploit animals for selfish gain.

Many animals from great mammals to microscopic insects have been killed in the name of science. This tends to be a pretty gray area and most people tend to have mixed feelings about it.

While one person can’t stop animal cruelty or exploitation, we can do our part in small ways to contribute to the overall problem. Many animal lovers refuse to buy goods that use experimentation on animals. We can all do our part in small ways to preserve the life of our fellow co-inhabitants.

History of Animals in Space

Laika wasn’t the last animal in space. In fact, an alarming number of animal species have been shot into the atmosphere. From flying insects to microscopic bacteria to chimpanzees, there have been plenty of species that have experienced space.

Many of the creatures that enter space have the same fate as Laika. They never return to Earth. However, some animals have made a full journey, continuing to live their lives once their feet hit the soil again.

Let’s do a little timeline!

1940s

- February 20, 1947—Fruit Flies (recovered)

- June 14, 1949—Rhesus Monkey “Albert II” (died on impact)

1950s

- August 31, 1950—Mouse (died on impact)

- July 22, 1951—2 Dogs (recovered)

- November 3, 1957—Dog “Laika” (died during flight)

- December 13, 1958—Squirrel monkey “Gordo” (died on impact)

- July 2, 1959—Two dogs, one rabbit—(recovered)

- September 19, 1959—2 frogs, 12 mice (died during launch)

- December 4, 1959—Rhesus Macaque “Sam” (recovered)

1960s

- August 19, 1960—Two dogs “Belka and Strelka”, a gray rabbit, 40 mice, 3 rats, 15 flasks of fruit flies, plants (recovered)

- October 13, 1960—Three black mice “Sally, Amy, Moe” (recovered)

- January 31, 1961—Chimpanzee “Ham” (recovered)

- November 29, 1961—Dog “Enos” (recovered)

- October 18, 1963—Cat “Felicette” (euthanized for experimentation)

- February 22, 1966—Two dogs “Veterok and Blackie”

- November 1968—Turtles (recovered)

1970s

- November 9, 1970—Two bullfrogs (recovered)

- April 16, 1972—Pocket mice “Fe, Fi, Fo, and Fum” (Died on trip)

- July 15, 1976—Tortoise, Fish (recovered)

1980s

- 1985—Two squirrel monkeys, 24 male albino rats, stick insect eggs

- 1989—Chicken embryos

1990s

- 1990—Guinea pigs

- December 1990—Quail eggs

- March 18, 1995—Newt

2000s

- 2003—Silkworms, garden orb weaver, carpenter bees, harvester ants, Japanese killifish (deceased)

- July 12, 2006—Madagascar hissing cockroaches, Mexican jumping beans

- September 2007—Tardigrades

- March 15, 2009—Free-tailed bat (accidental passenger)

2010s

- May 2011—Golden orb weavers “Gladys and Esmerelda”

- November 2011—Tardigrades

- January 28, 2013—Monkey

- February 3, 2013—Mouse, two turtles, worms (recovered)

- January 2014—Pavement ants

- July 19, 2014—Gold dust day geckos

- April 14, 2015—Mice

- April 8, 2016—20 mice

- June 29, 2018—20 mice

- April 11, 2019—Tardigrades

2020s

- June 3, 2021—Tardigrades, Hawaiian bobtail squid

Conclusion

Now you know a little bit more about how Laika contributed to space exploring. While she might have had a very short and difficult time on earth, we only hope she found solace over the Rainbow Bridge.

One thing is for sure, she will certainly go down in history as the first dog to journey into space. She definitely accomplished a lot in her short and tragic life.

Related Reads:

- What Kind of Dog Is in the Movie Dog? (Explained)

- What Kind of Dog is Doge from Dogecoin? Facts, Pictures & Breed Info

Featured Image Credit: Property of The New Yorker. All rights reserved to the copyright owners.