Regular walks are important for your dog, but the weather doesn’t always cooperate. No one is going to melt in the rain, but some dogs are bothered by it. There are other risks when it’s raining and wet, such as poor visibility near roads, outdoor chemicals, and more.

Whether you’re dealing with a drizzle or a torrential downpour, here are some tips for walking your dog in the rain to make the experience safe and fun for both of you.

The 7 Tips for Walking Your Dog in the Rain

1. Pay Attention to the Forecast

It’s smart to pay attention to the weather report before any walk, not just for rain. Walking your dog in extreme cold or severe thunderstorms increases the risks, including scaring your dog with thunder and lightning or the rare risk of electrocution.

If it’s just raining, consider how heavy it will be. Drizzles on an otherwise warm and bright day won’t be so bad, but a severe downpour may be worth waiting for. Low visibility can increase the risk of a car accident or flood areas. You should also consider your dog’s age and size. Older dogs and small puppies may struggle in areas with a lot of puddles or slippery spots.

2. Get Rain Gear

If you live in an area that gets a lot of rain, investing in a raincoat and rain boots may be worthwhile. Raincoats protect your dog from getting too wet and cold, and they make it easier for you to dry off when you go into the house.

Make sure you get the right size for your dog, especially when it comes to the boots. You should try these on before a rainy walk to get your dog used to them for short periods. Avoid leaving rainboots and a raincoat on for too long, especially after a walk, as they don’t breathe well. Your dog can overheat or develop a bacterial infection from the moisture.

3. Get Safety Gear

Your dog should already have reflective safety gear for walks at night or early morning. But if you don’t, make sure to get them. Something as simple as a reflective vest and leash with bright colors can help drivers see you and your dog in dreary conditions. You should also get a raincoat for yourself to make sure you’re visible.

4. Plan Your Route

You’re likely familiar with the area where you walk your dog, including what spots get deeper puddles or rushing gutters that can be hazardous. Consider alternative routes before you head out on your walk and what areas should be avoided, such as busy traffic areas, streets that may be washed out, or steep hills that can get slippery.

5. Take Short Walks

If the weather is bad, it’s okay to take a shorter walk and focus on your dog doing their business quickly. You can save the longer walks for nice days and focus more on indoor enrichment for the time being. If it’s going to be raining all day, take a lot of shorter walks throughout the day instead of a longer one.

6. Don’t Let Your Dog Drink from Puddles

Dogs aren’t nearly as picky as humans about their water sources. Puddles can be especially attractive, but try not to let your dog drink from them. Rainwater pools with dirt, debris, and bacteria that can be harmful to your dog, especially if you live in a city. Bring a water bowl and bottled water along and offer them that instead.

7. Be Prepared for Cleanup

A wet dog is more than a bad smell and muddy prints all over your floor and furniture—it can be dangerous for your dog. Plan your cleanup and prep your doorway with wet cloths, paw wipes, and dry towels. As soon as you come in, take off your dog’s rain gear and begin drying them off. Make sure you clean off their paws in between the pads and dry them thoroughly, either with towels or a blow dryer.

If you are looking for the perfect product to clean your dog's sensitive areas, Hepper's Wash Wipes are our recommendation, plus it's a great on-the-go option. These premium wipes are thick and durable enough for the toughest of paw messes, while still being soft enough to use on your dog's ears or eyes. Formulated with pet-friendly, hypoallergenic ingredients they are the ideal product for all dogs of all ages, skin conditions, or sensitivities.

- Gentle Care For All Pets - Infused with moisturizing hypoallergenic ingredients & enriched with...

- Deep Cleans From Head to Tail - Tackle the toughest dirt & messes with our extra strong pet wipes...

- Freshness On The Go - Each dog grooming wipes pack contains 30 counts of premium dog wipes that...

At Dogster, we’ve admired Hepper for many years and decided to take a controlling ownership interest so that we could benefit from the outstanding designs of this cool pet company!

What if My Dog Is Afraid of the Rain?

Some dogs like rain more than others, but a torrential downpour or thunderstorm with high winds, lightning, and loud noises can be daunting for any dog. If your dog is afraid of the rain, use rewards to encourage them to go outside. If your dog has a nervous or fearful temperament, you may want to avoid going out if the weather is severe. It can be difficult to control a reactive dog in these conditions.

Don’t make a big deal about the storm, and be patient. Let your dog adjust and keep offering treats for small wins. This is another good reason to keep the walk short and focused to avoid overwhelming your dog with the experience.

Conclusion

Walking in the rain may not be as fun as a dry, sunny day, but it only takes a few extra precautions to make it a fun and safe experience. If the weather is severe, just wait it out and play inside. Otherwise, enjoy a safe walk with the proper gear and smart decisions.

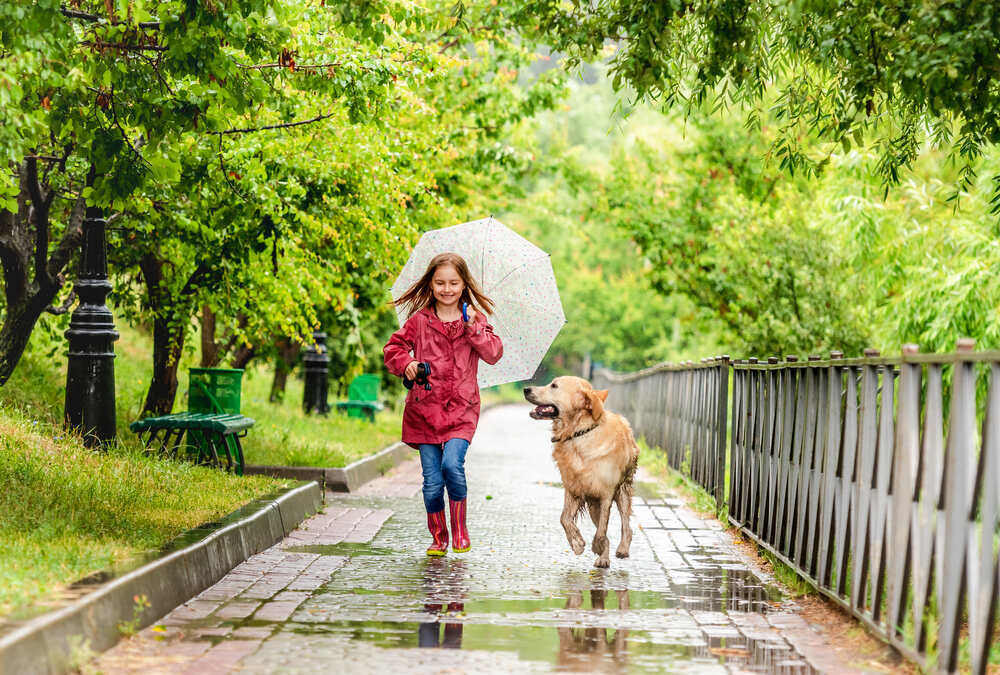

Featured Image Credit: Tatyana Vyc, Shutterstock